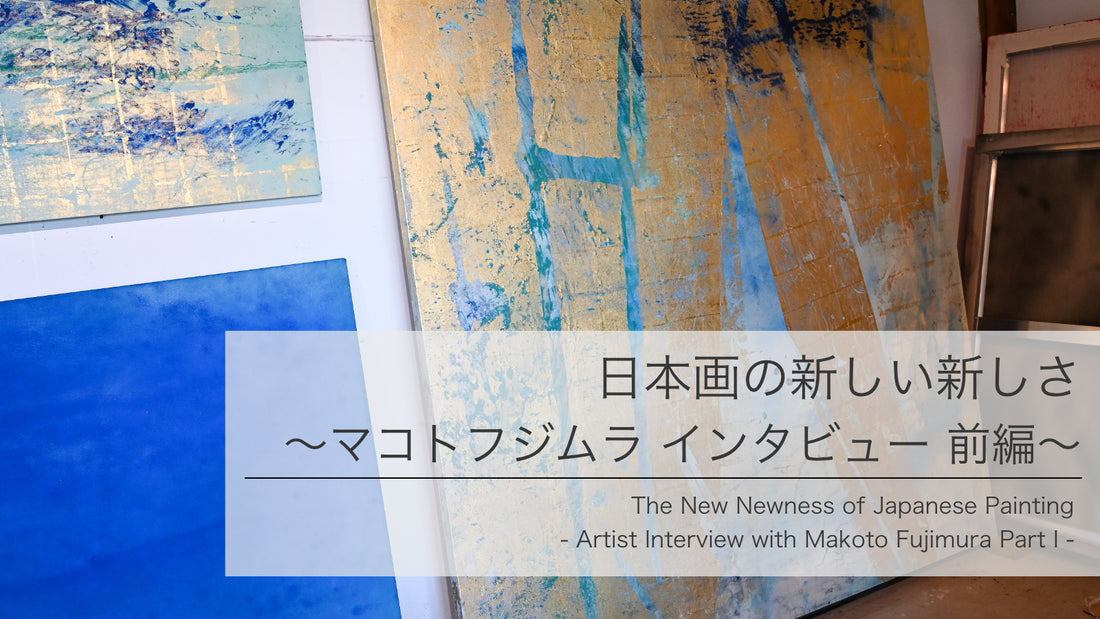

Makoto Fujimura is a Contemporary Artist using Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) materials living in the United States.

His activities are not limited to being an artist; as a survivor of 9/11, he has been involved in arts advocacy for victims of disasters, and his accomplishments led him to serve as an arts and cultural advisor to the White House under the Bush administration.

For this article, PIGMENT TOKYO visited his studio in New Jersey and interviewed him about how he became an artist, creating by using Nihonga materials in the U.S., and the aesthetics that arise from his view of the materials used.

ーI heard that you came to Japan as an international student, but how did you decide to come to Japan?

Makoto Fujimura ( hereafter Fujimura / titles omitted): I went to Bucknell University, a liberal arts school in the United States.

It was in Union County, Pennsylvania, and I had my studio around the area.

At that time, I used oil paints and other materials available in the U.S., but I always thought that water-based paint was more suited for my hands.

And my teacher was a watercolor artist who was one of the leading colorists in America.

Makoto Fujimura during this artist interview.

ーWould you describe him a little bit more?

Fujimura: His name was Neil Anderson. He is well known among watercolor artists and he seemed to admire Japan very much. One day, he asked me, "Have you ever been back to Japan?" When I answered, "No, I haven't since I was 13 years old," he said, "You have to go back.”

I was born in Boston and am an American citizen, but I went to school in Kamakura during elementary school, so I think my aesthetic originated there.

Later, when I was attending the Tokyo University of the Arts as an international student, I had many teachers and professors such as Kazuho Hieda, Matazo Kayama, and Norihiko Saito.

I also taught English conversation classes at that time, and Keizaburo Okamura, Hiroshi Senju, and Takashi Murakami were my students.

ーThat is truly the golden age of the 90s and early 21st-century Japanese-style painting.

Fujimura: While pursuing my Ph.D. in graduate school, Yuji Murakami was in the same studio with me, and I was always having discussions with him, as well as with Takashi Murakami.

Along with contemporary art and other mediums, "What is Japanese-style painting?" is still one of the agendas that are have been developed in many different ways.

Students who have spent their entire lives in Japan tend to look at Japanese-style paintings from biased perspectives.

I objectively believe that Japanese-style painting itself is wonderful.

Outside of his studio. His studio is located in the national park that allows him to create art surrounded by nature.

ーDo your experiences in Kamakura, which you mentioned earlier, have any influence on your current artworks?

Fujimura: I think it had a tremendous influence on me. When my mother passed away, I was in California, painting a large piece titled "Sea Beyond," using only white shell pigment powder called Gofun.

《Sea Beyond》Makoto Fujimura, year, size(cm),

Belgian linen, animal glue, white shell pigment

When I was painting this piece, I was in a town called Newport Beach, California.

I visited my daughter, who lived near there, and received the news that my mother had passed away.

I went to the beach early in the morning to think about all kinds of things. I looked at the horizon and wondered where was on the other side of it, so I looked it up and found it was Kamakura.

ーWow, it is destined to happen, isn't it?

Fujimura: What I recalled at the moment was how my mother cherished my act of painting itself. She seemed to have known for a long time that I was going to be an artist or get some kind of creative job.

When I lived in Kamakura, I spent my summers every day at the beach, and that was very much rooted in my sense of beauty. I think I knew with my sensitivity that she was going to pass away.

This work is in the European"Altar Piece" format, in which the centerpiece is placed higher in a series of three paintings when they are hung on a wall.

I guess the big question given to art is what can be "seen" beyond the horizon line, beyond our vision.

For me, it was the summer in Kamakura that I experienced as a child. In my case, it led to Japanese-style painting, and in this way to California.

ーI see your point. Is there a deep connection between Christianity and the art you create?

Fujimura: Interestingly enough, I became a Christian when I returned to Japan for my studies at the Tokyo University of the Arts.

ーOh, you had not been a Christian until then.

Fujimura: I kept wondering "Why did I come to Japan to become a Christian?" for a long time. After my mother passed away, I followed my ancestors and found that there were many hidden Christians in my ancestors on my mother's side.

I heard my maternal grandfather and grandmother were church leaders, but I did not make such a deep connection with them. But now it makes sense to become a Christian after I returned to Japan.

Going back to Japan, that was a "call ring."

ーThat sounds like another destined story.

Fujimura: During my MFA program at the Tokyo University of the Arts, I lived in the Futakotamagawa area, where there was a horizontal bridge similar to the one in "Sea Beyond," and I painted it as a motif for my thesis project.

Mineral pigments used for his artworks.

ーFrom there, it would relate to the story of Neos and Kainos, which was also explained in the video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEY22ixwfAQ

Fujimura: There are two Greek words Neos and Kainos in the Bible that means “new.”

Neos is just like a new iPhone; A year after a new iPhone is released, it becomes an old model. That is what Neos is.

Kainos is the “New Newness”. Saint Paul, one of the Epistle writers of the New Testament, said that the resurrection of Jesus Christ was a “New Creation”.

Not just like the new iPhone, but new newness, therefore, New Creation.

The resurrected Jesus had a scar, and I think that scar is quite important. Why was his existence not as a superman, but as a human being? Why did he resurrect not only as a human being but also as a wounded human being?

That is very close to the idea of Kintsugi (golden joinery). Kintsugi is not only for repairing to reuse but also for creating a new piece of art.

ーIt is not like buying a new plate or fixing them together with super glue.

Fujimura: Instead, they draw new lines with gold, and they even bond Korean and Japanese ceramics together with the concept of something like the peace-making process. It is not only in Japan but also in Korea, there is something unique about Eastern culture.

ーIs the notion of Kainos itself one of the philosophies behind the creation of your artwork?

Fujimura: Yes, that is right. I have been thinking about it for a long time. Especially after 9/11.

What came into my mind when I saw Ground Zero was first of all to respect the tragic victims there.

After that, the empty “Ground Zero“ looked beautiful. I felt the Japanese painting itself in the presence of the refracted beauty created depending on where the sun was coming out.

When the light hit the fallen buildings, something new emerged into space.

ーYou thought that you should not feel beautiful there.

Fujimura: Well, I am also a survivor of 9/11, so it is difficult for me to just express that feeling. I think that is why I seek healing to occur through my paintings.

If this experience is not connected to my future life, I will be traumatized, and it will become my identity as it is. So as a survivor, it is necessary to go through complicated processes.

ーIt is like Ground Zero did not return to its original building even after reconstruction.

Fujimura: I know it is the same for you. When I face my trauma, I instantly feel like I want to run away. However, as you continue therapy, you realize that trauma will never go away as your experience for the rest of your life. Then, healing will come to you for the first time.

People cannot get there easily, and that is what we are experiencing through COVID-19 and Ground Zero. We will not get back to a “normal” world after the pandemic is over.

ーWe will not return to normal life…

Fujimura: Yet, that is a reality of being a survivor. We are all survivors. It is important to recognize that. We cannot go back to normal. Healing will come to us when we realize that what we have experienced and suffered under the pandemic will remain as scars. However, when the healing comes, the question arises, "How do we renew the scars of the past?

If trauma becomes our identity, we will not grow. This is why I believe that the ways of thinking inspired by Kainos, the new newness, and Kintsugi are essential, especially from now on.

ーSince animal hide glue changes its form by heating it, it is quite Kainos, isn't it? Did such a way of thinking match the technique of Japanese painting?

Fujimura: Exactly, they matched. At first, I only grasped it with my intuition. I thought it was interesting. Professor Saito told me, "You are a quick learner." It seemed it was truly my thing because it took me only one month to master Japanese-style painting, which usually takes two years as an undergraduate student. That is why I think my experience in Kamakura was so significant.

Malachite mineral pigment kneaded in the mortar.

Fujimura experienced the beauty of Japanese-style painting firsthand through his childhood years in Kamakura.

The destined stories of his origins and the interaction between Japanese art materials and Christian aesthetics are very inspiring for me as someone who grew up in Japan.

The second half of the article will be featuring his artwork and the materials he uses.

Translated by Atsumi Okano

PIGMENT TOKYO Art Materials Experts