When you see or hear the word "Impressionism," what’s the first thing that comes to your mind?

If you live in Tokyo, you may be familiar with the Matsukata Collection, a permanent exhibition at the National Museum of Western Art in Ueno, Tokyo.

Other than that, many other exhibitions related to Impressionism have been held around us, and some people might consider Impressionism as synonymous with the art movement of the 19th century.

Then why do these impressionist paintings continue to fascinate people?

Impressionist painters captured phenomena and sensations with their eyes and transferred the impression in their minds to the canvas through their lively brush strokes.

These "impressions" that remained on the canvas continue to attract viewers like us today, even after centuries.

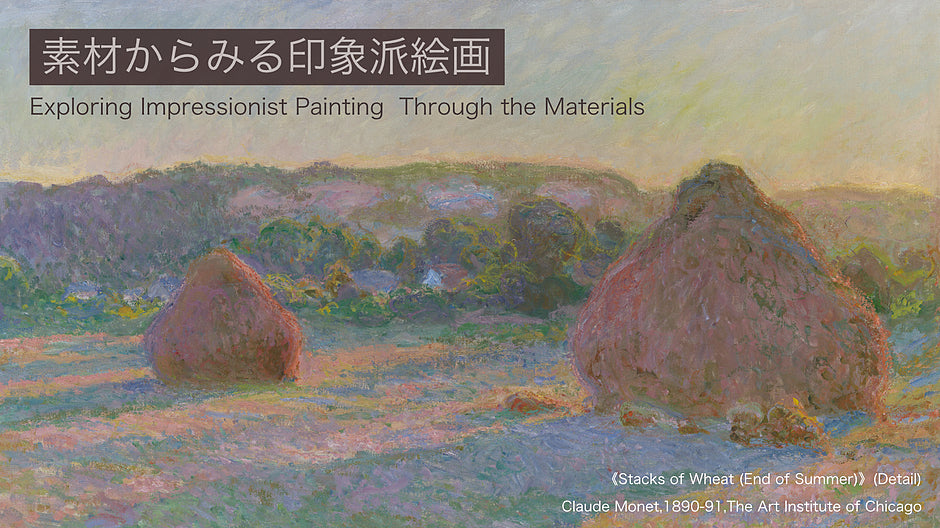

For instance, let’s take a look at this painting.

《Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer)》Claude Monet,1890-91,The Art Institute of Chicago

The myths of religious figures and legends of historical figures that were once significant milestones of European painting are no longer present.

Instead, only the plein air landscapes of the countryside depicted with fuzzy colors and brush strokes remained.

By eliminating the outlines and details of the motifs, Claude Monet probably wanted to keep their objective elements away from the viewers.

At the same time, he beautifully captured the soft light that almost reminds me of when I see the outside world through squinted eyes because it is too bright.

Claude Monet aimed to create "light paintings" which depicted these natural phenomena.

So why did he explore light in his paintings?

One of the answers could be that he was passionate about exploring the visual sense. For example, he painted a number of the same motifs, such as "Grainstacks," "Poplars," "Rouen Cathedral," and "Water Lilies.”

These paintings were not mass-produced in just different color palettes, like Warhol's "Campbell's Soup Can," but painted at different times of the day, seasons and even weather conditions.

In the "Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry," the 17th-century critic Lessing noted that "I think that the single moment of time, to which the material limits of art confine all its imitations, will lead to such considerations." Also, he spoke about how a painter can only paint one moment from one perspective means that the viewpoint capturing the moment must be carefully chosen.

Indeed, the light of the natural world presents us with different scenery depending on the day.

Claude Monet honestly faced such physical restrictions and depicted the phenomena created by nature in the changing seasons.

What makes his expression of light so distinct is his talented painting technique but also, there are the secrets of the materials used by these Impressionist artists.

Let's have a closer look at the painting.

《Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer)》(Detail) Claude Monet,1890-91,The Art Institute of Chicago

This piece is painted with impressive brush strokes just to capture the very moment when natural light was hitting the straw.

In that case, tube paints are essential for artists to do this kind of outdoor painting.

Back then, artists only ground the necessary amount of pigment each time, then knead it with oil to create oil paints in the conventional painting studio.

And of course, it was impossible to create a painting with only one color, so it required an enormous amount of labor and time.

Moreover, if artists wanted to paint the scenery as Monet did, they had to carry all kinds of materials and tools to their painting location.

In other words, if they wanted to make outdoor paintings using only hand-made paints, they would probably lose the day just by carrying a marble stone board and pigments everywhere.

Picture from the PIGMENT ARTICLES “Let's Make Oil Paints with Oil Color Medium”

Plein air painting became more practicable in the early to mid 19th century because of the development of oil paints in tubes, which allowed painters to carry them outdoors with ease.

As the name implies, these paints need to be kept in containers like tubes, and if the viscosity of the paint is too low, leaks can occur during travel. Therefore, even today, if you want to fill an empty tube with your hand-made oil paint, you need to adjust the viscosity a little higher by adding filler.

That’s why some people think that the idea and inspiration for Claude Monet's thick brushstrokes come from the invention of these paint tubes.

Another secret is the use of minimally primed canvases.

Many paintings in both Western and Asian are painted on a substrate after applying a primer.

Although there are various purposes for doing so, such as preventing absorption and improving the fixation of mediums, priming is almost indispensable, at least to increase the durability of the artwork.

Let’s take a look at the photo of a lime ground panel used for fresco painting, one of the classical techniques. Lime ground with limestone and silica sand has been applied underneath the painted surface, and then sized linen fabric can be seen on the sides.

You can see how the painting fabric changes before and after the ground coating.

However, when it comes to Claude Monet’s paintings, are treated and primed rather minimally.

Next, let’s take another look at a different part of the same painting.

《Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer)》(Detail) Claude Monet,1890-91,The Art Institute of Chicago

We can see the canvas showing through at the bottom corner of the painting.

Since the weave is visible and its color is a little brownish, it suggests that the canvas was not ground coated with plaster or other white-based extender pigments.

I assume it allows the oil paint to soak into the canvas, creating a gradual soft color texture.

Furthermore, thanks to the unevenness of the canvas weave, it catches the paintbrushes and holds paints better, so the painters can create powerful strokes on the canvas.

There is no doubt that Monet's aesthetic sense and technique were incredible, but there were also hidden secrets in the materials he used, which made it possible to create optical phenomena on canvas without being bound by traditional theories.

PIGMENT TOKYO offers many workshops that approach fundamental painting methods, such as traditional paint-making and the use of metal leaf.

These art experiences from a materials science perspective, which cannot learn only from art history books, will surely deepen your understanding of art.

Therefore, don’t forget to check on PIGMENT TOKYO's workshop page to find out more fun opportunities!

References

・Heinrich Lützeler, “Abstract Malerei — Bedutung und Grenze,” translated by Hideho Nishida (Bijutsu Shuppansha,1973).

・Lessing, "Laocoön - On the Limits between Painting and Poetry," Translated by Eiji Saito (Iwanami Shoten, 1970).

・Makoto Miyashita, “Deviant Painting (Lectures on 20th Century Art)” (Houristu Bunkasha, 2002)

Matsukata Collection, National Museum of Western Art (viewed November 16, 2021)

https://www.nmwa.go.jp/jp/about/matsukata.html

Column" History of Tube Paints (viewed November 16, 2020)

https://www.craypas.co.jp/press/feature/009/sa_pre_0016.html